About the Author

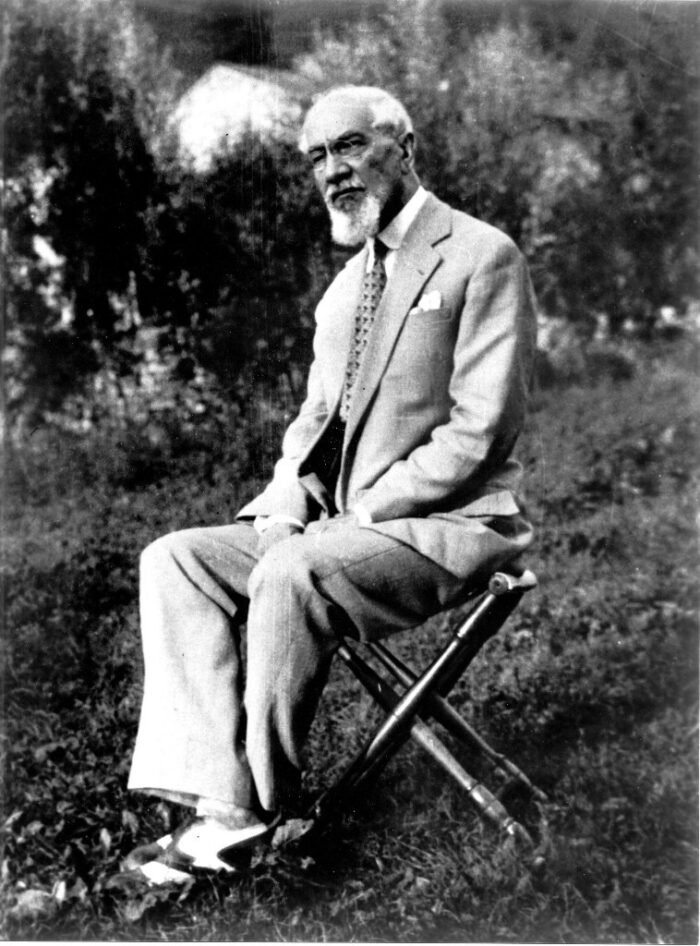

Luigi Natoli (1857-1941)

Luigi Natoli (1857-1941) patriotic and fervent republican, teacher, journalist, scholar of history, and called “the last of the archetypal popular writers” was the author, in addition to a great number of histories, critical essays, poems, theatrical texts, and schoolbooks, of thirty-one serial novels, published under the pseudonym William Galt. Through them he set out to compose an epic of the freedom of the Sicilian people. Among those that stand out, in addition to the legendary I Beati Paoli, are the sequel Coriolano della Floresta, and Calvello il Bastardo.

At the age of three he was imprisoned, together with his entire family, in the Vicaria prison in Palermo, because his mother had dressed her children in red shirts in order to greet Garibaldi’s arrival in Sicily. Everything the family owned was confiscated or burned. “The family risked dying of hunger, if not for the mercy of a prison guard, who every so often secretly brought them a bowl of pasta and beans. ‘I was saved by a plate of beans,’ Natoli recalled”. [1] Their strained financial circumstances haunted him until his last days but contributed to the development in him of a most deeply rooted and fervent freedom of thought and expression. As a child he frequented libraries, became an auto-didact, and as his talent for writing blossomed, he began writing for the Giornale di Sicilia.

At twenty-three, he taught Italians in gymnasiums (junior high schools). Forced by circumstances to travel all over Italy, from Rome, — where he stayed three years — to Pisa, Sardinia, and Naples, everywhere he went he socialized in literary circles. He became friends with other Italian writers, including Federico De Roberto, Luigi Capuanna, Salvatore Di Giacomo, and Giuseppe Pitrè. Fervently secular and anticlerical, he worked indefatigably and cultivated his passion for history and culture, in particular for that of Sicily, dividing his time between work commitments — which could not be postponed because of the need to support a very large family — and frequent visits to historical archives and libraries. His assiduous and intense study of the Sicilian history and the vicissitudes that forever troubled the island, instilled in him a profound feeling toward his homeland that permeated his writing, and he maintained a prodigious literary output throughout his lifetime.

[1] Gabriello Montemagno, L’Uomo Che Inventò I Beati Paoli (Palermo: Sellerio Editore, 2017, 19-20).

In his will, he wrote:

“I didn’t pursue my work for commercial gain, but only for the joy that it gave me.”

The Flaccovio Edition

From his two marriages (his first wife died very young; the second, Teresa Gutenberg, the daughter of the man who became his publisher) he had several children. He educated them on the basis of the same approach to culture and study that he had put into practice with his own students, one inspired by moral rectitude, which could be implemented by being faithful to the principles of respect for everything and everyone (including different political beliefs), of loyalty and honesty. It so happened that his children, raised by the same principles of education, ended up with different political convictions, and all of them led lives of great fervor.

His rejection of Mussolini and the fascist regime resulted in the banning of some of his books. But until his last breath, Luigi Natoli opposed the abuses of those in power. And to the priest who, in his last days of life, promised to remove his books from the ban as long as he agreed to withdraw the book on Fra Diego La Matina — in which he tells how embezzlement between the Spanish rulers and the clergy brought about the condemnation of the friar to the stake by the Inquisition — he gave his most firm refusal, encouraging him to tell his superiors that “history cannot be recalibrated or covered with a veil. And neither he nor the Pope have such power”. His rich literary production gave him great fame but little financial benefit.